Every year, hundreds of thousands of people in the U.S. get infected with MRSA - a stubborn type of staph bacteria that won’t respond to common antibiotics like penicillin or amoxicillin. What most people don’t realize is that there are two very different kinds of MRSA: one that spreads in hospitals and another that spreads in the community. They look similar on the surface - red, swollen, painful bumps on the skin - but their origins, behavior, and treatment are worlds apart. And the line between them? It’s disappearing fast.

What Exactly Is MRSA?

MRSA stands for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. It’s not a new germ - it’s just a version of the common staph bacteria that evolved to survive antibiotics. When methicillin was introduced in the 1950s, it wiped out most staph infections. But some bacteria mutated, developed resistance, and survived. Those survivors passed on their resistance genes. Today, MRSA doesn’t just resist methicillin - it shrugs off most penicillin-based drugs, including oxacillin and amoxicillin.

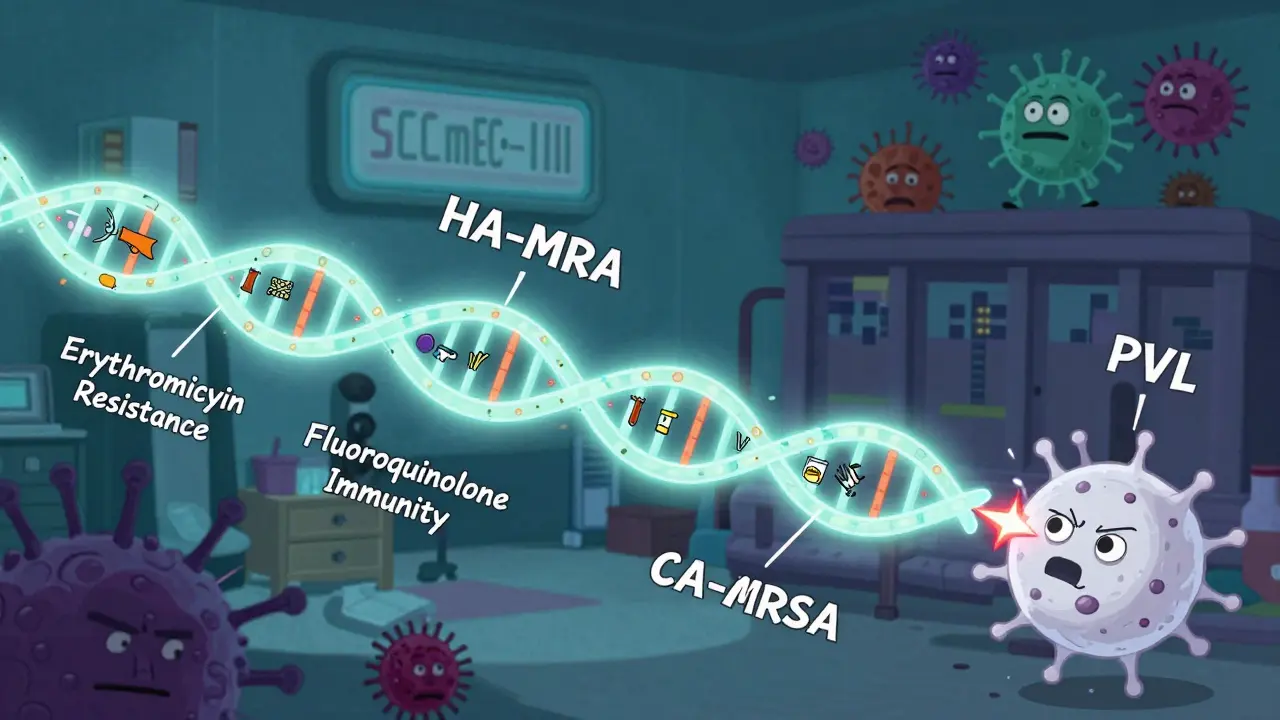

Here’s the catch: not all MRSA is the same. Two major types exist - one born in hospitals, another in everyday life. They’re genetically different, spread differently, and need different treatments. Confusing them can mean the wrong medicine, longer illness, or even life-threatening complications.

HA-MRSA: The Hospital-Born Strain

For decades, MRSA was called a hospital-only problem. That’s HA-MRSA - hospital-associated MRSA. These strains emerged in the 1960s and thrived in places where antibiotics are used heavily: ICUs, surgical wards, dialysis centers, and nursing homes.

HA-MRSA carries large chunks of DNA called SCCmec types I, II, or III. These chunks don’t just give it resistance to methicillin - they pack in resistance to nearly every other antibiotic too. Up to 98% of HA-MRSA strains resist erythromycin. Two-thirds resist clindamycin. Over 90% resist fluoroquinolones like ciprofloxacin. This makes treatment a nightmare. Doctors often have to use last-resort drugs like vancomycin or linezolid, which are expensive, harder to administer, and can damage kidneys or nerves.

Patients who get HA-MRSA are usually already sick. They’ve had surgery, a catheter, or a ventilator. Their immune systems are weak. Infections often go deep - bloodstream infections, pneumonia, or surgical site infections. Hospital stays for HA-MRSA patients average over three weeks. Many end up in intensive care. And because these strains are so resistant, they linger on surfaces, on gowns, on hands - making outbreaks hard to stop.

CA-MRSA: The Community Strain That Changed Everything

In the late 1990s, something unexpected happened. Healthy teenagers, athletes, military recruits, and parents with young kids started showing up at clinics with painful, pus-filled boils. No hospital visits. No recent surgeries. No IV lines. Just a red, angry bump on the leg or back that didn’t get better with over-the-counter creams.

This was CA-MRSA - community-associated MRSA. It wasn’t just spreading. It was winning. The key difference? Smaller DNA chunks - SCCmec types IV and V. These don’t carry as many resistance genes. So CA-MRSA is often still sensitive to clindamycin (96% of cases), trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (92%), and tetracyclines like doxycycline (89%). That’s good news. It means simpler, cheaper, safer antibiotics can work.

But here’s the scary part: CA-MRSA is more aggressive. Many strains produce a toxin called Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL). This toxin kills white blood cells, turning a simple skin infection into a deep, fast-spreading abscess - or worse, necrotizing pneumonia. A healthy 22-year-old athlete can go from a small pimple to a breathing tube in 36 hours.

USA300 is the most common CA-MRSA clone in the U.S. It’s responsible for about 70% of all community cases. It thrives in crowded, sweaty, skin-to-skin environments: wrestling mats, gyms, dorm rooms, prisons, and homeless shelters. In prisons, the risk is nearly 15 times higher than in the general population. Injecting drug users are a major reservoir - sharing needles, poor hygiene, and broken skin make transmission easy.

Where Do They Meet? The Blurring Line

Here’s the reality no one wanted to admit: the two types aren’t staying in their lanes anymore.

People with CA-MRSA get hospitalized. They bring the strain inside. Meanwhile, HA-MRSA escapes into the community through discharged patients or healthcare workers. A 2017 Canadian study found that nearly 28% of MRSA infections acquired in hospitals were actually caused by community strains. And 27.5% of community cases came from hospital strains.

This isn’t a glitch. It’s a system failure. Hospitals discharge patients with MRSA still on their skin - sometimes for months. These patients then spread it at home, at school, at the gym. Meanwhile, community strains like USA300 are showing up in ICU beds, carrying their toxin genes into hospitals where they can infect vulnerable people.

And it’s getting worse. In some hospitals, CA-MRSA is now the top cause of new MRSA infections. That means the old rule - “if it’s in the hospital, it’s HA-MRSA” - doesn’t work anymore. A patient who never set foot in a hospital for a year can still get a hospital-acquired MRSA infection. And a patient with a catheter can get a strain that’s never been seen inside a hospital before.

How Are They Treated Differently?

Treatment isn’t one-size-fits-all. The wrong choice can cost you weeks - or your life.

For CA-MRSA skin infections, the first step is often not antibiotics at all. Doctors will drain the abscess. That’s it. Many patients recover fully without any pills. If antibiotics are needed, clindamycin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline are first-line choices. They’re affordable, well-tolerated, and still effective in most cases.

HA-MRSA? It’s a different story. These infections often go deep. Bloodstream infections, lung infections, bone infections - they need strong, IV antibiotics. Vancomycin is the go-to, but resistance is creeping in. Newer drugs like daptomycin or linezolid are used, but they’re costly and come with side effects. Treatment lasts weeks. Recovery is slow.

Here’s the problem: if a hospital doctor assumes every MRSA case is HA-MRSA, they’ll give vancomycin to someone who just needs drainage and doxycycline. That’s overkill. It wastes resources. It harms the patient’s gut bacteria. And it fuels more resistance.

On the flip side, if a community doctor sees a severe infection in someone who recently had surgery and assumes it’s CA-MRSA, they might give clindamycin - only to find out the strain is resistant. The infection spreads. The patient ends up in the ER.

Why the Old Definitions Are Outdated

The CDC’s old definition of CA-MRSA was simple: if you hadn’t been in a hospital in the past year, it’s community-acquired. But that’s broken now.

A 2008 study showed that this rule fails more than half the time. People with no hospital history can carry HA-MRSA strains. People with multiple hospital stays can carry CA-MRSA. The bacteria don’t care about your medical record. They care about genes, toxins, and who they touch.

That’s why experts now say we need to stop labeling by location and start labeling by strain. Genetic testing can tell you if it’s USA300 (likely CA) or ST239 (likely HA). But most clinics don’t do this. It’s expensive. It takes days. So doctors guess. And guessing kills.

What Can You Do?

Prevention is your best defense - whether you’re in a hospital or at home.

- Wash your hands often. Soap and water beats hand sanitizer for MRSA.

- Keep cuts and scrapes covered until they heal.

- Don’t share towels, razors, or athletic equipment.

- If you’re in a gym, wipe down equipment before and after use.

- If you’re in the hospital, ask staff to wash their hands before touching you.

- If you’re discharged with MRSA, follow cleaning instructions. Wash clothes in hot water. Disinfect surfaces you touch.

And if you see a skin infection that’s red, hot, swollen, and getting worse - don’t wait. Don’t pop it. Don’t ignore it. See a doctor. Early drainage can save you from months of antibiotics - or worse.

The Future Is Integrated

We’re no longer dealing with two separate MRSA problems. We’re dealing with one interconnected threat. Hospitals can’t control MRSA by just sterilizing their walls. Communities can’t stop it by just telling people to wash their hands.

The solution? A unified system. Hospitals need to screen patients not just for recent stays, but for risk factors like incarceration, drug use, or recent sports injuries. Community clinics need better access to rapid testing. Public health agencies need to track strains, not just locations.

Right now, we’re fighting MRSA with 1990s tools. The bacteria moved on decades ago. It’s time we did too.

Can you get MRSA from a toilet seat?

It’s possible, but unlikely. MRSA survives on surfaces for days, but transmission usually requires direct skin contact with an infected wound or sharing personal items like towels or razors. Toilet seats aren’t a major source unless someone with an open sore uses it and another person touches it with broken skin right after. Hand hygiene is far more important than worrying about seats.

Is MRSA always dangerous?

No. Many people carry MRSA on their skin or in their nose without any symptoms - this is called colonization. It only becomes dangerous if the bacteria enter the body through a cut, wound, or medical device. In healthy people, it often causes mild skin infections. In those with weak immune systems, it can lead to life-threatening infections.

Can MRSA be cured completely?

Yes, most MRSA infections can be cured with proper treatment - drainage, antibiotics, or both. But clearing the bacteria from your skin or nose (colonization) is harder. Some people remain carriers for months or years, even after an infection heals. This doesn’t mean they’re sick, but they can spread it to others. Decolonization treatments (like nasal ointment and body washes) can help, but they’re not always effective long-term.

Why is CA-MRSA more common in prisons?

Prisons are perfect for MRSA spread: overcrowding, poor hygiene, frequent skin-to-skin contact, shared showers and towels, and high rates of cuts and abrasions. Injecting drug use is common, and needle sharing introduces bacteria directly into the bloodstream. Studies show prison inmates are nearly 15 times more likely to get CA-MRSA than the general public.

Does antibiotic use in farms contribute to MRSA?

Yes, but indirectly. Antibiotics used in livestock can lead to resistant bacteria in animals. Some strains of MRSA (like CC398) have jumped from pigs to farmers and meat processors. These are different from the USA300 strain that dominates human infections, but they show how antibiotic overuse anywhere can fuel resistance that eventually reaches people.

Comments (8)

Gregory Parschauer

Let’s be real-this isn’t just about MRSA strains, it’s about systemic negligence. Hospitals treat patients like disposable widgets, discharge them with colonization, and then act shocked when CA-MRSA shows up in the ICU. And don’t even get me started on the lack of genetic sequencing in community clinics. We’re diagnosing with guesswork while bacteria evolve like fucking superheroes. This isn’t medicine-it’s triage roulette. The CDC’s outdated definitions are a death sentence wrapped in bureaucracy.

Alan Lin

While I appreciate the thorough breakdown of HA-MRSA versus CA-MRSA, I must emphasize that the clinical implications of misclassification remain grossly under-addressed in primary care settings. The reliance on epidemiological history rather than molecular characterization constitutes a critical diagnostic gap. Furthermore, the overuse of vancomycin in empiric regimens for skin and soft tissue infections-particularly in the absence of systemic signs-contributes directly to the emergence of VISA and VRSA strains. A paradigm shift toward point-of-care PCR or MALDI-TOF in urgent care centers is not merely advisable-it is imperative.

Robin Williams

bro. i just had a boil last year. doc drained it, gave me doxy. i didn’t even need a script. but my buddy? he went to the er with a fever after a surgery and got vanco for 3 weeks. same bug. different world. why do we still act like hospitals and gyms are separate planets? we’re all connected. skin to skin. sweat to sweat. needle to needle. the bacteria don’t care about your insurance card. they just wanna live. and we’re giving them the keys to the kingdom.

Scottie Baker

Y’all keep acting like this is some new crisis. Nah. This is capitalism. Hospitals cut corners. Pharmacies push profit over prevention. And the poor? They’re the ones getting stuck with CA-MRSA in prisons and shelters while the rich get IV antibiotics in private rooms. You think they’re testing inmates for SCCmec types? Nah. They’re just throwing antibiotics at the problem like it’s a damn sprinkler system. And guess what? The bacteria laugh. They’ve been laughing since penicillin.

Anny Kaettano

Thank you for highlighting the PVL toxin and the role of USA300-this is exactly what we need to be teaching frontline providers. But let’s also talk about equity. If we’re going to push for rapid genetic testing, we need to fund it in community health centers, not just academic hospitals. I’ve seen patients in rural clinics wait weeks for culture results while their abscesses spread. We can’t wait for perfect diagnostics when prevention and early drainage are so effective. Let’s train nurses to recognize the signs, empower community health workers to educate on hygiene, and make decolonization protocols accessible. It’s not just about science-it’s about justice.

Kimberly Mitchell

Handwashing won’t fix this. You can’t sanitize systemic failure. The entire medical infrastructure is built on reactive, not preventive, care. We treat infections like personal failures instead of public health emergencies. And now we’re blaming patients for bringing CA-MRSA into hospitals? That’s not science-it’s scapegoating. If hospitals can’t contain what they produce, they shouldn’t be allowed to discharge patients without mandatory decolonization protocols. Simple. Non-negotiable. No more excuses.

Angel Molano

Stop overcomplicating it. CA-MRSA is aggressive. HA-MRSA is resistant. Mix them, you get worse outcomes. Test the strain. Treat accordingly. Stop guessing. Done.

Vinaypriy Wane

Thank you for this comprehensive, deeply informative post-it has clarified many misconceptions I held about MRSA transmission dynamics. I would like to add, however, that the role of livestock-associated MRSA (e.g., CC398) in human colonization is often overlooked in U.S. discourse, particularly in regions with intensive farming. While it may not dominate human infections like USA300, its zoonotic potential underscores a broader, global pattern: antibiotic misuse in agriculture directly undermines clinical efficacy. We must advocate for policy reform at the intersection of veterinary medicine and public health, not merely focus on hospital and community silos. This is a planetary issue, not a local one.